Announcing the All-New 2024 Tesla Douchemobile

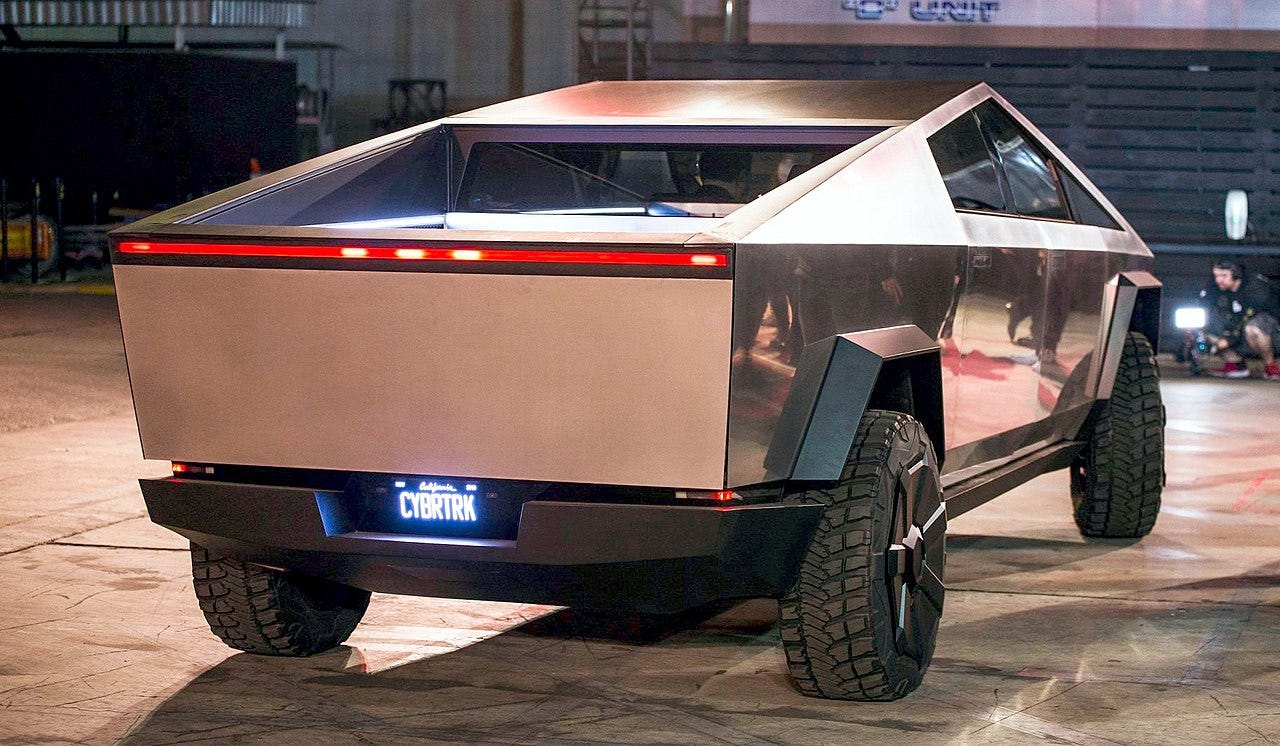

The preposterous Cybertruck, and what our cars say about all of us.

There may be no vehicle currently for sale in the United States of America more freighted with symbolic and cultural meaning than the Cybertruck, the pickup that Elon Musk and Tesla finally unveiled last week after numerous delays and embarrassing pratfalls. In order to understand the Cybertruck, we have to consider what pickups in general represent in our culture, and how they’re tied up with masculinity, class, and the rural/urban divide.

This is a topic I spent a good deal of time thinking about as Tom Schaller and I reported and wrote White Rural Rage: The Threat to American Democracy, which will be on sale in February. I want to tell a quick story we relate in the book. As we were reporting in the Texas hill country, we had a conversation with a man in his 70s, and the subject of pickups came up. This took place in Fredericksburg, which is in a rural area but is itself a lively tourist town full of restaurants and shops.

Our friend said that when he was a kid, he hated it when his father picked him up at school in his pickup, because it showed that his dad was just a laborer, not someone of high social standing. But today if you head down the main drag in Fredericksburg, you’ll see the streets lined with pickups, and they symbolize exactly the opposite. They’re shiny, hulking monsters filled with plush seating, infotainment systems, and every other amenity you could want.

All that comes at a price. The most popular pickup in America is the Ford F-150, and the fancier trim packages on the truck can run nearly $100,000. There are even F-150 models that go as high as $150,000. Today, owning one of those tricked-out pickups is most definitely supposed to communicate high status. These were the top selling vehicles in America last year:

Ford F-series pickup

Chevrolet Silverado pickup

Ram pickup

Toyota RAV-4

Toyota Camry

GMC Sierra pickup

Four of the top six are pickups. The F-series, Silverado, and Ram have been numbers 1,2, and 3 for years. Yet the majority of pickups sold in America are not working vehicles. You can see that in the way they’ve changed shape over the years, with the bed — the part you use for work — getting smaller to accommodate comfortable back seats, even as they’ve gotten taller and more imposing.

Yet the conceit of a F-150 or Silverado is still that this is a work vehicle. Even if you aren’t actually using it for work, you could, and you could do the manly things with it that men do when they’re working with their trucks: hauling, towing, easily surmounting off-road obstacles. The pickup is a symbol of strength and manhood, displaying its owner’s mastery over the physical world. He does what he wants, drives where he wants, and if you get in his way he just might crush you.

While men (yes, mostly men) in all kinds of places buy pickups, their image is still rooted in rural notions of masculinity, which involve not only physical labor but practical competence and self-reliance. It’s why there are so many country songs about trucks in general and pickups in particular that they almost constitute their own subgenre. And it’s why, although pickups are now marketed in no small part to suburban dads, that marketing still works to evoke rural masculinity, something you can get a piece of by buying a truck no matter who you are.

Though it has lots of power, the idea that anyone would use a Cybertruck for the kind of manly occupations portrayed in typical pickup marketing is preposterous. Just imagine the chorus of guffaws that would greet a construction worker who pulled into a jobsite in this Douchemobile.

Or imagine you were a single woman, and you went out on a date with a man who told you midway through the meal that he’s planning to buy a Cybertruck. Would you think, “Oh, what an interesting fellow he must be!”

No, you’d think he was part of that dwindling population of Elon Musk superfans, young men who like to think of themselves as bleeding-edge techno-slicksters, yearning to one day become masters of the universe even if their current jobs are depressingly prosaic. Since boring their acquaintances with endless lectures about the genius of crypto has become socially problematic, they’re happy to deliver a similarly soul-deadening lecture about how awesome the Cybertruck is.

If you want to learn all the reasons why Musk’s decisions about what it would look like and how it would be built were absurd, I’d recommend this piece by Ryan Cooper at the American Prospect. But suffice to say that the Cybertruck is essentially Elon Musk in vehicular form: innovative in some ways, but also enacting a loudly performative stupidity, sure that it’s super-cool and a source of envy while most everyone in the world looks at it and laughs.

There were plenty of people who became uneasy about their Teslas when Musk began turning himself into the world’s most powerful right-wing internet troll, buying and setting out to destroy Twitter, then embracing conspiracy theories and anti-semitism. Back when the image a Tesla projected was one of technological sophistication, concern about climate change, and wealth, it was all good. But these days it’s hard to see a Tesla and not think immediately of the company’s edgelord CEO.

The Cybertruck isn’t inherently less practical than any other pickup, or any car for that matter. You could use it to haul and tow, even if most of its owners won’t. But most pickup owners don’t use their vehicles for those things, either; they like the image their pickups project. Every car says something to the world about its owner, and the inescapable message sent by the Cybertruck, at least for now, is “I’m an insufferable man-child who actually thinks Elon Musk is a role model.” If that’s the message you want to send, go right ahead. But don’t be surprised when most people turn away in disgust.