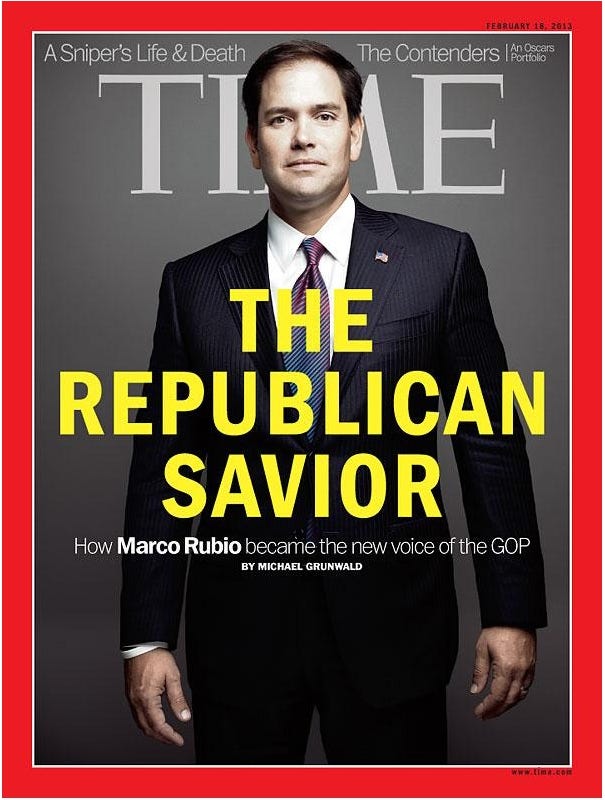

There are some expressions that come to define a politician — Bill Clinton’s squinty-eyed concerned-yet-empathetic face, George W. Bush’s impish grin, Barack Obama looking grandly over an adoring crowd as though the Music of Destiny was swelling beneath him. For Marco Rubio, the defining expression is one of pained unease. There he is in the Oval Office, sitting uncomfortably in silence, his eyes cast down and his body tense, as the president to whom Rubio has pledged his labor and his dignity goes about mucking everything up yet again. Or in the photo above: dressed in his embarrassing mini-Trump costume (blue suit, red tie), looking down while his master says one more dumbass thing.

As Rubio tells his own family’s story, he is here today because America is a beacon of freedom and opportunity for the world. He may not be the “son of exiles” as he used to say at the beginning of his career — his parents came to America in 1956, three years before Fidel Castro mounted his communist revolution in Cuba — but the powerful gravity the United States exerts on the oppressed and the ambitious around the globe is the reason he grew up in Miami and not Havana, and the reason that today he is Secretary of State.

So it’s particularly striking to see Rubio become the chief implementer of Trump’s effort to withdraw America from the position it used to occupy in the world, in both practical and symbolic terms. Rubio’s whole career — in fact, his whole life — is a testament to the ideas he has decided to help this president destroy.

So what happened to him?

How he got here

Rubio was elected to the Senate in 2010 at just 39 years old, after a rapid rise through the Florida legislature. Among the collection of right-wing extremists and yahoos who took office that year, he stood out as someone with a limitless future. Young, smooth, smart and eloquent, his was just the image the GOP wanted to convey. In a 2013 cover story (back when that was still an extremely big deal), Time magazine called him “the Tea Party’s answer to Barack Obama.”

He was everything the Republican Party wasn’t: young, bilingual, urban, and seemingly in touch with pop culture; in his early years in Washington he would quote hip-hop lyrics while addressing the Senate. But he was also a staunch conservative, both on social issues and foreign policy. As the son of Cuban immigrants, he could embody the GOP’s opposition to communism and the need to project strength around the world. More than anything else, he could be a kind of translator, explaining Republican conservatism to constituencies that didn’t appreciate it yet.

But things started going wrong later that year, with the failure of the immigration reform he and a bipartisan group of senators called the Gang of 8 had negotiated. It passed the Senate, where he and other Republicans saw it as a way to solve not only the immigration policy problem but what they saw as their political dilemma. In a country growing more diverse by the day, they couldn’t be a majority party unless they expanded their appeal beyond white voters, and reforming immigration could show the rapidly growing Latino population in particular that they should consider the GOP as a home.

But the bill died in the House amid opposition from the right, and Rubio was soon vilified as a traitor in the conservative media that had seen him as one of their own.

He ran for president in 2016 anyway, and found that the embrace he received six years earlier was really an elite phenomenon. It wasn’t just that Donald Trump had a compelling image shaped by the unreality of his reality TV show, it was that at a fundamental level, the Republican base wanted what Trump was selling — the anger, the resentment, the bigotry, all of it. Rubio couldn’t keep up, and his final humiliation was this desperate ad he aired as his campaign was circling the drain:

“This election is about the essence of America, about all of us who feel out of place in our own country,” he said, which was bizarre coming from someone whose whole appeal was supposed to be that he didn’t feel out of place in the new, diverse America.

So close, and yet so far

With the Oval Office still in his dreams, Rubio continues to struggle to keep up with a Republican Party that not only grows more and more radical, but does so in ways that are specifically opposed to who Rubio is and what he is supposed to represent. And if he thought that in joining the Trump administration he could make it more closely represent his own views about foreign policy, he couldn’t have been more wrong. Instead, Rubio has become more pathetically submissive than ever, and with worse effects.

Consider what he is doing now in the context of his immigration story. After questions were raised about whether he had claimed falsely that his parents fled Castro’s dictatorship (which carries a lot of weight in Miami politics), Rubio defended himself in a 2011 article in which he wrote, “The essence of my family story is why they came to America in the first place; and why they had to stay.” He went on: "I am the son of immigrants and exiles, raised by people who know all too well that you can lose your country. By people who know firsthand that America is a very special place.”

But the essence of the Trump foreign policy is that this isn’t a special country, not really. We have no admirable values that lift us up, no particular principles, no desire to foment the spread of liberty. We are not trying to be a beacon to the world, because we don’t want the world to be drawn to us. We’re just one more ruthless competitor in an international viper pit, and whatever we gain will be only at others’ expense, because we’re bigger and stronger than they are. And if people elsewhere see something in America that they want to be a part of, well too bad; we’re closing our doors. The entrepreneurial striver watching our TV shows in Asia and dreaming of making it big in business in America, the brilliant young science student in Europe who wants to go to MIT? This administration sees them not as an opportunity, but a threat.

So it is now for Marco Rubio, whatever he may have said before. Working against the forces of oppression is no longer a goal, let alone a priority, in his State Department. He has gutted the office that used to advocate for human rights, and as Marisa Kabas reported, he is creating an Office of Remigration to coordinate expulsions, using a term common among far-right groups in Europe focused on getting rid of non-white immigrants.

Then there’s the terrible story of the U.S. Agency for International Development, for which Rubio was one of the strongest advocates as a senator, arguing that the agency was vital not just to save lives but to serve America’s interests. “I promise you it is going to be a lot harder to recruit someone to anti-Americanism and anti-American terrorism if the United States of America is the reason one is even alive today,” he said. Rubio has presided over the dismantling of USAID, ending support for health clinics, humanitarian food aid, and our ability to show struggling people around the world that America will be there for them in their darkest hours.

In defending the administration, Rubio has dismissed the substantial research and reporting showing that the abrupt withdrawal of American aid has resulted in thousands of deaths from malnutrition and disease (one estimate puts the number above 300,000). “No one has died because of USAID” he said, calling the idea “a lie.” I can’t help but think his angry response is the sound of a man trying to pound the last vestiges of his conscience into submission.

And now Rubio is playing a key role in the administration’s efforts to target foreign students for expulsion, for expressing opinions the administration doesn’t like, or just being from China (last week Rubio announced that the State Department will “aggressively revoke visas for Chinese students”). He also ordered all embassies and consulates to cease conducting interviews with prospective students, which are required before they can obtain student visas. It appears that the administration’s intent is to expel as many foreign students as possible, and close the country’s doors to those who want to study here in the future.

The world is full of highly influential people who studied in America, some of whom have become prime ministers and presidents, such as Muhammad Yunus in Bangladesh (Ph.D. in economics from Vanderbilt) or Ellen Johnson Sirleaf in Liberia, the first female elected head of state in Africa (BA from the University of Colorado, master’s degree from Harvard). The purpose of attracting students from overseas is not only that highly talented young people might stay and contribute to American progress (true) or that we’ll benefit from them while they’re here (also true), but that they will return to their home countries and tell others about what they saw in the United States. They’ll extoll our freedoms, our spirit of innovation, and our cultural dynamism to their family, friends, and colleagues. They’ll become seeds of pro-Americanism which spread through their cultures, horizontally to other citizens and vertically through their key institutions.

That’s the kind of soft power Marco Rubio used to believe in. Maybe he no longer believes it, and he is sincere when he defends every awful thing he does to realize Trump’s dark vision of an America that has no true allies and looks at the world with nothing but fear and contempt. Or maybe he still believes in what America was supposed to represent, but he believes in his own presidential ambitions even more.

Without reading his mind, we can’t know for sure. But at some point, if the work you do every day is so destructive, not only do your good intentions no longer matter, it becomes difficult to believe those intentions were ever real.

Perhaps Rubio was always a creature of pure ambition, one who never believed in anything more than his own advancement. He certainly wouldn’t be the first. But for all his political talents, he can’t quite hide the fact that he knows how repugnant the man he serves is, and how terrible are the sins he now commits in that man’s service. It’s written all over his face.

Thank you for reading The Cross Section. This site has no paywall, so I depend on the generosity of readers to sustain the work I present here. If you find what you read valuable and would like it to continue, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

I would argue that it’s not about what “happened to Rubio”, who actively participated in everything that has “happened” to him. From my perspective it’s more about you coming to grips with realizing that Rubio was never the person you had imagined him to be. 🤷🏻♀️

Body language tells it all. His humiliation is there for all to see — his sad face, downward cast eyes, slumped posture. All of which tells me he KNOWS! Pathetic.